In the verdant cradle of Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, where the river winds like a delicate filament, a silk was born quietly, purposefully. Known as Lãnh Mỹ A or lacquer silk, this material once defined an era of refinement in Vietnamese dress. With a surface as smooth as polished stone and a black so profound it seems to hold light rather than reflect it, the fabric was not only worn, but lived in, its presence quietly commanding, its making an act of devotion.

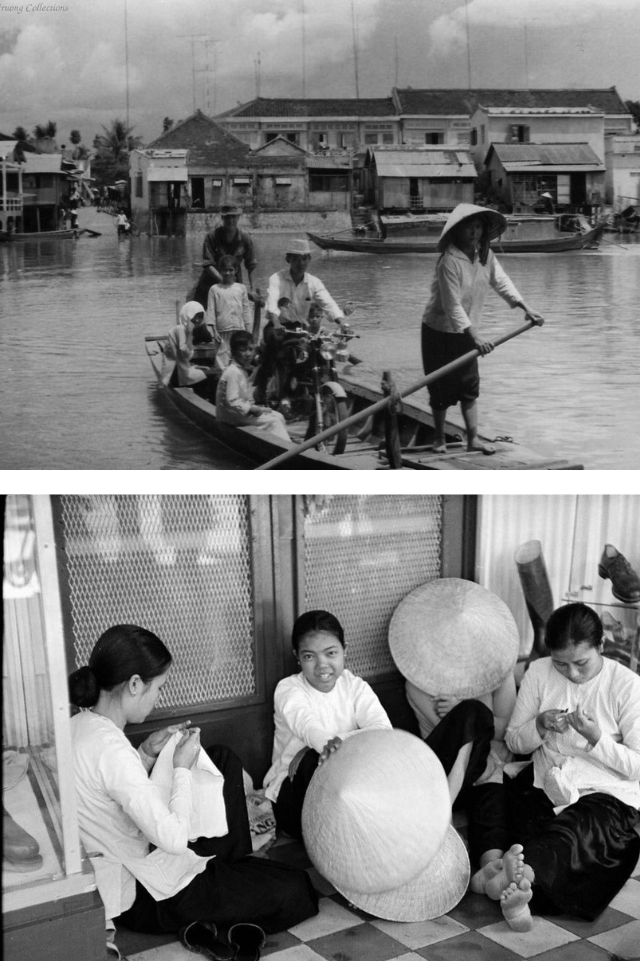

To trace the origin of Lãnh Mỹ A is to journey to Tân Châu, a small town along the Cambodian border where craft and patience once intertwined in daily life. In the early decades of the 20th century, this riverside community became known for its silk farms and dyeing houses, where techniques were honed over generations. By the 1950s, this fabric found its way into the wardrobes of Saigon’s most discerning women. Its deep black, paired with the elegant form of the áo dài, expressed a kind of poised clarity, opulence yet grounded in tradition. Its laborious production and refined finish made it a rarity, accessible only to the wealthiest families of the time. A single length of Lãnh Mỹ A spoke of privilege, of cultural taste, and of a connection to heritage expressed through material sophistication.

Credit: Christopher Ness 1969 (first picture) – LIFE magazine 1950 (second picture)

Though its origins lie in the French colonial period, Lãnh Mỹ A remained unmistakably Vietnamese: rooted in restraint, shaped by ancestral skill. And yet, the name Lãnh Mỹ A remains as enigmatic as the fabric itself. Even the last remaining artisans, including Nguyễn Văn Long, affectionately called Tám Lăng, confess uncertainty – “No one knows exactly why it’s called Lãnh Mỹ A.” Some suggest the name reflects a form of classification or early branding. Others believe it carries the trace of a name, perhaps of a woman, a place, or a story long obscured.

Yet the significance of Lãnh Mỹ A is not in what it is called, but how it is made.

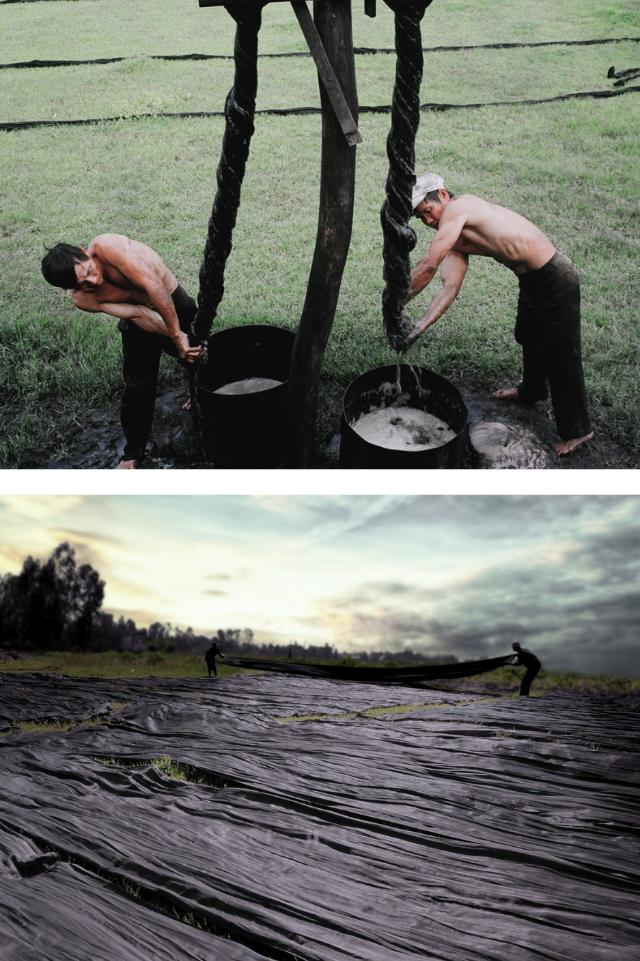

Crafted from mulberry silk of the highest quality, the fabric is dyed with mặc nưa, a black resin extracted from the Diospyros mollis tree. The dyeing process is both technical and ceremonial: repeated immersions, sun-drying, and rinsing are carried out no fewer than thirty times across a span of forty days. What results is a black of rare depth, layered with undertones of ink, wood smoke, and earth. It is not simply dark; it is dimensional. Once dyed, the fabric is steamed, beaten, and polished entirely by hand. No chemicals. No shortcuts. Only heat, pressure, and precision. The result: a silk of elegance, dense yet fluid, matte yet gleaming. It resists wear, yet yields effortlessly to the form, its tactile quality rivalling leather, its visual signature unmistakably singular across Southeast Asia.

Credit: Dang Quang Vinh (first picture) – Heritage magazine (second picture)

Yet time has not always been kind to this textile. The upheavals of the 1970s – war, the rise of synthetic fibres, and the gradual loss of mặc nưa trees – disrupted the ecosystem that once supported the fabric’s creation. Workshops closed. The knowledge, once passed from parent to child, began to fade.

Only one voice remained: that of Tám Lăng. A meticulous, soft-spoken artisan, he chose to continue, not for commerce, but for continuity. “We do not weave to become rich,” he says, “but to preserve our soul.” Each length of his silk requires weeks of manual care. Each centimetre holds time, memory, and a refusal to forget.

Credit: Heritage magazine

Today, as fashion shifts toward deeper meaning, toward craftsmanship, origin, and deliberate process, Lãnh Mỹ A finds quiet resonance once more. Designer Nguyen Cong Tri has brought the textile back to the contemporary stage, allowing its distinctive qualities to be reinterpreted through a modern lens. In motion, the fabric does not just shimmer. It recalls lost forests, disciplined hands, and a devotion that transcends time.

Precise, unembellished, and honest, Lãnh Mỹ A invites us to consider the measured. In rediscovering this silk, we are reminded that forward movement sometimes begins by looking back with care, with reverence, and with intent.